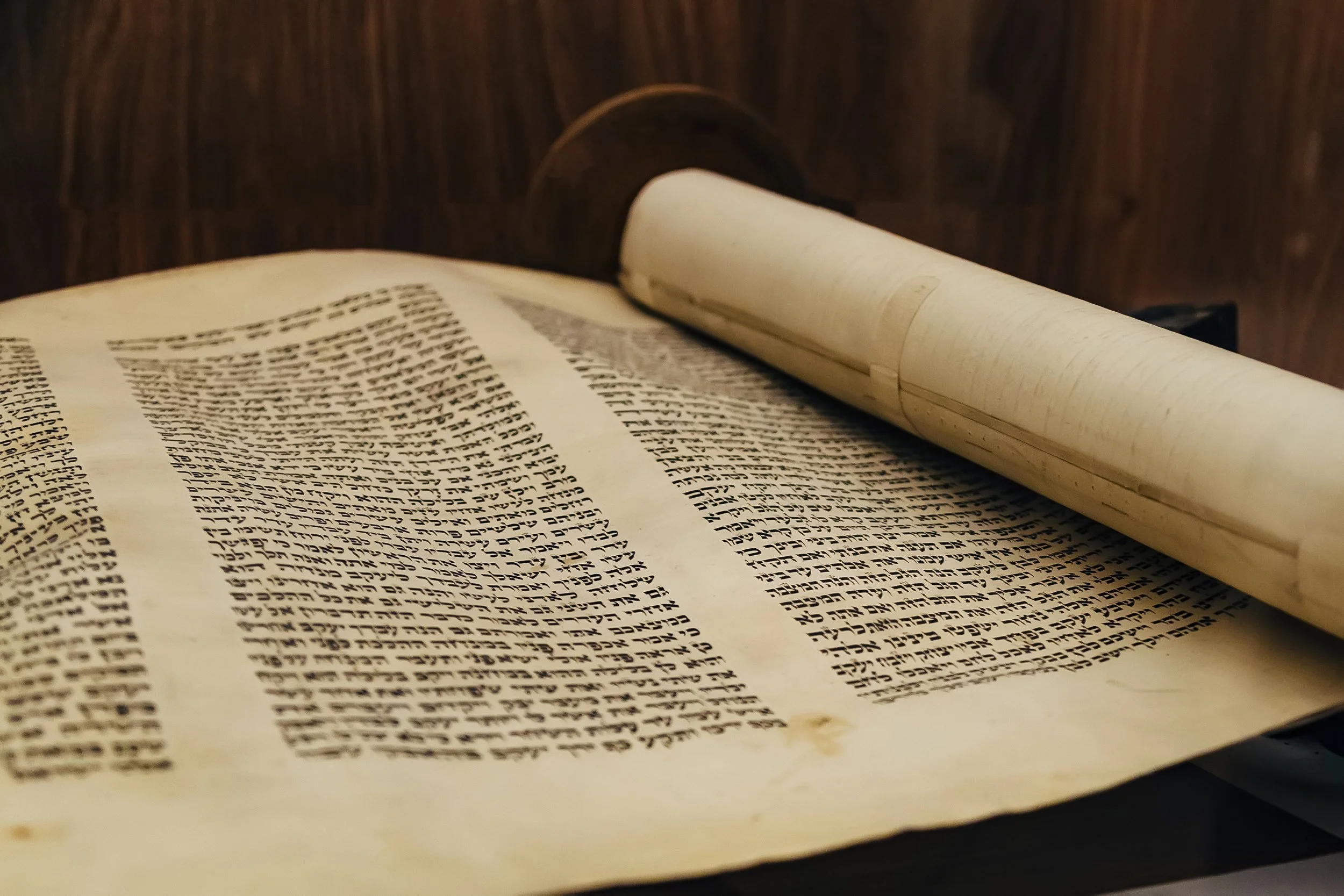

Old Testament Teaching Outlines

The journey from bondage in Egypt to worship at Sinai represents, in a general sense, the redemption of all of God’s elect: from slavery, to salvation, to service.

In the end, this book of beginnings points us to Jesus: the Lion of the tribe of Judah (cf. Rev. 5:5), the true King of Israel (cf. John 1:49), the Lamb of God for Isaac (cf. John 1:29), the ever-present friend of Abraham (cf. 2 Chron. 20:7), the ark of Noah’s salvation (cf. 1 Pet. 3:19-21), the life-giving last Adam (cf. 1 Cor. 15:45), and the Creator of the world (cf. Col. 1:16).

Just as these sacred songs were adept at leading the nation of Israel in the worship of God, so too are they today—whether in song or in sermon—for those in the Church.

Cataloguing the nineteen men who reigned next, the Chronicler traced the downfall of Judah not only to point out the tragic cause of exile, but more importantly, to bolster his point to the returnees that they were serving a God who does not forget His people.

Indeed, these repatriates could trust that the God who worked wonders for their ancestors would continue to do so for them and their descendants. Hope for the future had returned, and the Chronicler was determined to use history to prove it.

On the other hand, if we recognize that God works all things “according to the counsel of His will” (Eph. 1:11) and “for good to those who love God” (Rom. 8:28), we can begin to search for God’s purpose in our pain. And that vital truth sets the tone for the rest of the book.

Far from being a random assembly of disparate sayings, Solomon skillfully ordered the sequence of his work into a number of intentional collections, or groups. Like links in a chain, each proverb contains its own strength, but also contributes to the strength of a greater discourse.

The three major sections to this book poetically picture the meeting, marrying, and maturing of Solomon and his bride (“the Shulammite,” cf. Song 6:13), corresponding well to the “leave, cleave, and weave” paradigm of marriage that God established (cf. Gen. 2:24).

In order to rebuke the sins of the skeptical, encourage the hearts of the hopeless, and correct the errors in their eschatology, God sent yet another prophet—Malachi (meaning “my messenger”)—who would serve as God’s final spokesman to the nation before what would become four hundred years of silence.

Emotion soon became ambition, as Nehemiah determined that he would lead an effort to rebuild the walls. Yet, far from conjuring up these plans from his own intellectual genius, it was actually God who exercised His sovereignty over Nehemiah by putting the very plans into Nehemiah’s mind (cf. Neh. 2:12).

As one of the most quoted Old Testament books in the New Testament, the fulfillment of Zechariah’s prophecies concerning the first coming of Christ ought to instill both great confidence and great joy in those of us looking forward to Christ’s second coming.

In His kindness, God raised up Haggai for a short four-month, four-message ministry to turn the hearts of His people back to Himself.

And so it is that with an incomplete return, inferior temple, and immoral nation, the truth becomes even more evident that only the Son of God—the Lord Jesus Christ—can restore Israel (cf. Acts 1:6).

Thus, this narrative is not of good people doing good things for a good outcome, but of a good God bringing about a good outcome through sinful people.

Through a series of dreams and visions, God revealed to Daniel not only much about His predestined plans for the future, but much about the coming one world ruler who would try (unsuccessfully) to stop them.

So it was that Ezekiel comforted them with a promise that God would seek out His sheep, destroy their enemies, regenerate the heart of the entire nation, and—in one of the most memorable illustrations of salvation—raise an entire valley of dead bones back to life. In other words, there would be a day in which God would single-handedly grant spiritual revival to all Israel (cf. Rom. 11), just as He does in the life of each individual who comes to saving faith today.

Yet, in spite of their sin, God had not forgotten about His people—nor His enemies (cf. Lam. 3:59-66). With such an exalted view of God, it’s no surprise that in 1925, Thomas Obadiah Chisholm (1866-1960) wrote the famous hymn “Great Is Thy Faithfulness,” based on the third lament in this book.

Just as a potter can reshape a spoiled jar, so too could God reshape the nation (cf. Jer. 18:6). And in fact, God promised He would do just that. There would indeed come a day in which God would provide a New Covenant, one that—unlike the Mosaic Covenant—would be permanent, personal, and perfect (cf. Jer. 31:31-37).

The evidence that Habakkuk understood all of this is found in the final chapter, in which Habakkuk uttered a lyrical, liturgical prayer expressing that he indeed would trust God no matter the circumstances.

As divine warning shots, those past acts of judgment merely foreshadowed the judgment that God still has yet to unleash upon the earth. Zephaniah prophesied that there is coming a time in which the whole earth will be consumed (cf. Zeph. 1:18).

Unlike Jonah, who was a messenger of grace to the city of Ninevah one hundred years prior, Nahum was a messenger of judgment. Writing decades before the fall of Ninevah, during the reign of King Manasseh in Judah, Nahum not only predicted the outpouring of God’s wrath upon Assyria, he pronounced it—and for good reason.

Aside from the Psalms, no other book is referenced in the New Testament as much as the book of Isaiah. Thus, whether you are familiar with Isaiah’s prophetic word or not, your theology has been heavily influenced by it.

Although this book is among the better-known accounts in Scripture, its meaning is not. To the secularist, this is nothing more than a ridiculous story of an impossible event. To the very young, this is nothing more than a fanciful tale of a strange event. But to the born-again student of Scripture, this is a miraculous account of a sovereign God.

Most do not consider the major questions in life until they are at the very end of it—just like Solomon. But those of us who have God’s Word, particularly as it is recorded in the book of Ecclesiastes, possess an unmatched treasure that makes us wise beyond our years (cf. Psa. 119:99).

As you teach through this wonderful text, you have the distinct privilege of pointing out the one who fulfills Micah’s message of hope: the Lord Jesus Christ—who is the good shepherd of His sheep (cf. John 10:11), the godly king from eternity and Bethlehem (cf. John 1:1, Matt. 2:5-6), and the great high priest who expiated the sins of His people (cf. Heb. 10:11-12).

Buying her back from the market for the price of a slave (fifteen shekels of silver and a homer and a half of barley being the equivalent of 30 shekels called for in Mosaic Law, cf. Exod. 21:32), Hosea’s redemption of his wife provides a breathtaking picture of God’s love for, and faithfulness to, His people.

Like the Apostles, Amos had no theological credentials (cf. Amos 7:14)—he was not a prophet (no formal role in prophesying) nor the son of a prophet (no formal training in prophesying), just as they were uneducated and untrained men (cf. Acts 4:13). But, like the Apostles, Amos was compelled to speak the message he was given, just as they were (Acts 4:20). And what a message it was.

As the shortest book in the Old Testament, one would think that Obadiah would be among the more familiar passages of Scripture. Sadly, such is not the case. And because Obadiah was preaching primarily to an ancient pagan nation (one of only two minor prophets who did so—the other being Jonah), the modern reader might see little of value in this short prophecy. But again, such is not the case.

This book offers a stark depiction of God’s wrath (cf. Joel 2:15-18), a compelling description of true repentance (cf. Joel 2:13), and a hopeful declaration of future blessing (cf. Joel 3:18).

The book of Leviticus, using cognate forms of qadosh more than one hundred times, emphasizes the holiness of God like no other. And in so doing, it gives the answer. Under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, Moses wrote Leviticus to help the Israelites understand the holiness of God, the sinfulness of man, the means of atonement, and the supremacy of the Great High Priest. It helps us just the same, today.